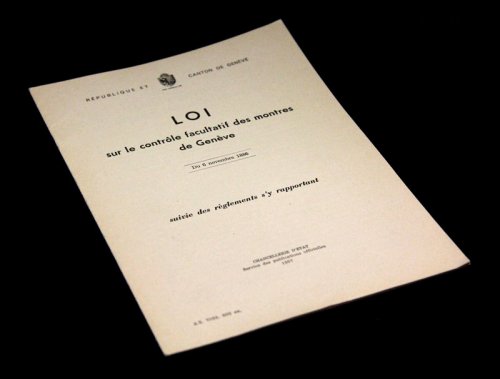

1. Law I 1.25

In 1886, the GRAND COUNCIL of the Republic and Canton of Geneva passed Law I 1.25 on the voluntary testing of watches in response to the obvious need for high-quality certification in watchmaking, covering the craftsmanship, regularity and durability of operation, and certificates of origin. In December 2008, the Law relating to the Geneva Laboratory of Horology and Microengineering was updated to raise the bar of horological excellence even higher.

2. Summary of the law

The State of Geneva delegates to TIMELAB - the Geneva Laboratory of Horology and Microengineering (hereafter Laboratory), which covers three distinct activities, the operation of:

a) the Poinçon de Genève Office, responsible for:

- the voluntary control of watches made and assembled in the Canton of Geneva, notably by marking watches submitted by Geneva-based manufacturers with the official stamp of the State of Geneva, according to the criteria set out in the Poinçon de Genève rules.

- the drawing up or authentication of certificates of origin, or the placing, for Poinçon de Genève watches, of a special mark;

b) the Observatoire Chronométrique +, responsible for the official testing of chronometer functioning and for certifying that the watches and/or the watch movements submitted meet the chronometer criteria1 and testing rules defined by its technical committee appointed;

c) the Horlogical Laboratory, responsible for a testing office for the watchmarkers

3. History

Proposed on 6 November 1886 by the Geneva government, the Law on the voluntary testing of watches was not done by half-measures. Firstly, it involved setting up an inspection office for Geneva-made watches. This was responsible for placing the official State mark on watches submitted by Geneva-based manufacturers. Most importantly, watchmakers who submitted watches for the Poinçon had to be residents of Geneva. This is because too many of them had moved abroad, and so the aim was to keep the expertise within the region. The Poinçon was then marked on a part of the movement (on the baseplate and a bridge) that was as visible as possible. For the other watches, the Office issued or authenticated certificates of origin.

3.1 The Technical Commission and its rules

Watches that received the stamp were those which, after examination, were found to have “all the qualities of craftsmanship to ensure regular and long-lasting operation.” To ensure oversight of the highest standard, the Control Office was placed under the management of a commission made up of a State Councillor, who also acted as its president, and 12 members: six appointed by the Council of State and six by the Grand Council.

These 12 members were (re)elected every other year. The Commission was responsible for determining the level of quality of the various technical parts of the watch, as well as the minimum number of those that had to be made by craftsmen based in the Canton of Geneva.

The Ruling of 26 March 1887 that followed was just as rigorous. In its first articles, it stipulated that the Office for the voluntary inspection of watches would be responsible for examining and stamping movements, attaching a “mark” (a stamp bearing the official imprint, attached by a cord) to the pendant of the case of an inspected watch, and issuing or authenticating certificates for watches stamped “which achieved a good result in operational tests carried out by the inspection office.” Furthermore, the latter had to “carry out all the necessary promotion to make the creation of a Geneva Office of Watch Control known in Switzerland and abroad.”

3.2 Certificate

The certificate issued had to contain “a description of the watch movement, its manufacture number, the inspection stamp and the responsibility statement signed by the manufacture in case of manufacturing defect.” Anyone found to have copied, counterfeited or falsified a Poinçon or certificate was punished under the terms set out in the Penal Code article.

3.3 Approved employees

The rules were just as exacting when it came to approved employees. They had to be from Geneva. Their roles consisted, respectively, of examining the movements, carrying out stamping and operational tests, and producing copy and advertising material. They were not allowed to make watches for personal purposes or to be involved, directly or indirectly, with the sale of the watches. They had to inform the president of the Commission immediately of any breaching of the law on the Commission’s inspection, rules or decisions.

3.4 Territoriality and examination of operation

To complete the picture, we should mention the criteria specified by the management commission of the Office for the voluntary control of watches in the Canton of Geneva. As well as underlining the fact that movements must be made according to the theoretical principles of watchmaking, its articles specified that manufacturers should supply all information that may be requested of them concerning the making of movements submitted for inspection. Concerning the “minimum requirement of work carried out by employees living in the Canton of Geneva”, this referred to the following parts: escapement, escapement setting, setting, repassage and adjustment. The guarantee of workmanship was stated in writing and signed by workers or special workshop managers and manufacturers. The tests consisted of examining the functioning of the watch in horizontal and vertical positions and in extreme temperatures. The minimum time allowed for these observations was six days.

Clearly, Geneva watchmakers were preparing to do battle. They were ready to conquer the 20th century, and proclaim their victory. Vacheron Constantin and Patek Philippe were the first “manufactures” to benefit from the prestigious label.

1 1. A ce jour, les accréditations sont délivrées par le Service d’Accréditation Suisse (SAS) dépendant du SECO en remplacement de METAS